In recent years there has been a lot of discussion around the final millennia of Neanderthals in Europe. Various sites across Spain are key to determining exactly when this human species died out, and how skilled they were.

The difference between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals appears to narrow every year as new writing on the topic emerges. There is a deluge of books, scientific papers and exhibitions that focus on the Neanderthals and challenge what we believed to date.

The Neanderthals lived in Asia and Europe, though not in Africa, for at least 300,000 years. They had been considered ‘distant cousins’ of Home sapiens but in 2010, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, sequenced the genome of Neanderthals for the first time. Their findings, that up to 2% of the DNA in the genome of present-day humans outside Africa originated in Neanderthals or in Neanderthals’ ancestors, suggest that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interbred. Spanish writer Juan José Millás and paleoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga wrote a philosophical book on this topic, La vida contada por un sapiens a un neandertal (Life as Told by a Sapiens to a Neanderthal).

Neanderthals not as primitive as first thought

The image of knuckle-dragging hominoids is disappearing when considering Neanderthals. Research negates the idea of zero communication, and knocks the ‘superiority’ of Homo sapiens down a peg or two.

As Rebecca Wragg Sykes, a British archaeologist and writer, said in an interview with El País, “Neanderthals have changed our perception of ourselves. In Western culture we have always tried to separate ourselves from the rest of nature, to prove that we are better than animals. Neanderthals force us to rethink that.”

Geraldine Finlayson told the BBC, lots of preparation went into the seemingly simple artwork. “It wasn’t something that happened by a mistake or as a result of a doodle… some thought process was going on,” she said.

When archaeologists tried to re-create the design, they found the deepest groove required 60 strokes of a sharp stone tool. “It was clear it was something intentional,” Geraldine continued.

Art and language

Discoveries of decorative shells and the use of red ochre pigment at Neanderthal sites is food for thought when considering the

Quite possibly the most convincing scientific evidence of Neanderthals being more advanced was the discovery of the FOXP2 gene in their DNA. Associated with language, the presence of the FOXP2 gene means they had some method of communication. The animals they hunted, reinforces this idea as they would have required group cooperation to be successful. That requires communication.

Finally, the societal behaviour of the human species shows advanced thought process. They made use of plants they found, they used stones for tools, buried their dead and took care of their elders. Not so different from Homo sapien behaviour today.

As John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told National Geographic in 2019, “Neanderthals appear to have had a cultural competence that was shared by modern humans. They were not dumb brutes; they were recognisably human.”

Why did Neanderthals die out?

The majority of researchers believe the Neanderthals disappeared abruptly around 40,000 years ago. However, some believe they continued to exist in the south of the Iberian peninsula, especially Gibraltar, for thousands of years after.

In January 2020, El País reported that Neanderthals took refuge in southern Spain and Portugal, following discovery of a footprint in Gibraltar. Dated from 28,300 years ago – much later than the date put forward for Neanderthal demise – it promteped a rethink.

Not only was there a hominoid footprint, but also elephants, goats and felines. However, there are no traces of Homo sapiens. Does that put to bed the theory that competition between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals oversaw the demise of the latter?

Inbreeding may have been a factor

A team from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands put forward a theory published in journal, PLoS ONE.

“Our results indicate that the disappearance of Neanderthals might have resided in the smallness of their population(s) alone,” reads the abstract of the paper written by Krist Vaesen, Fulco Scherjon, Lia Hemerik and Alexander Verpoorte. “Even if they had been identical to modern humans in their cognitive, social and cultural traits, and even in the absence of inter-specific competition, they faced a considerable risk of extinction.”

The risk of extinction may well have been due to the Neanderthal’s inbreeding. The presence of Neanderthal DNA in humans today proves they did breed with Homo Sapiens; however, not sufficiently to guarantee their survival.

Forced further south due to climactic change, the Neanderthals’ small societal groups meant there was a lack of diversity. A 2019 finding also proposes Neanderthal fertility was declining, perhaps due to lack of food. The research paper, led by Anna Degioanni from the Aix-Marseille University in France, proposed that even “a slight change in the fertility rate of younger females could have had a dramatic impact on the growth rate of the Neanderthal [population] and thus on its long-term survival”.

This, as Clive Finlayson told the BBC, means it was simply a matter of time. Their population may have become so small that eventually they reached “a point of no return”.

Spain – an important site for Neanderthal research

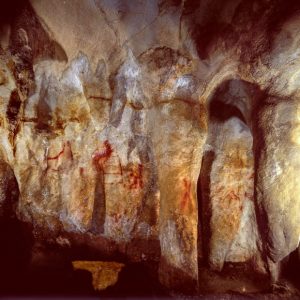

Spain is one of the richest sites for Neanderthal research. National Geographic reported in 2019 that in three caves across the country, researchers found examples of wall paintings over 65,000 years old.

Related post: History of Spain – Part 1, the Prehistory and Antiquity (until 1000 B.C.)

Gibraltar’s caves, which thanks to the rock’s geography are relatively undisturbed, is constantly researched. Caves across the south of Spain, continually throw up discoveries that test the latest theories on Neanderthal existence and extinction.

Where to find more information

Below, you’ll find a selection of museums and websites that provide a fascinating insight into Neanderthal existence and human evolution.

Gibraltar Museum has an interesting section on Neanderthals including a TV series (see episode 1 below).

Museum of Human Evolution, Burgos

Cuevas de los Letreros, Almería