The majestic snow-capped mountain peaks of the Sierra Nevada are timeless eyewitnesses to the fortunes of the Alpujarras. A fertile and green oasis in the otherwise rugged, mountainous environment in the southern Spanish region of Andalucia.

Despite a turbulent past, there are few signs of the passage of time in this region today. The seasons still dominantly determine the rhythm of the residents here. The last Moors living in Spain left a clear mark on the area, where they felt safe for another century in otherwise Christian Spain.

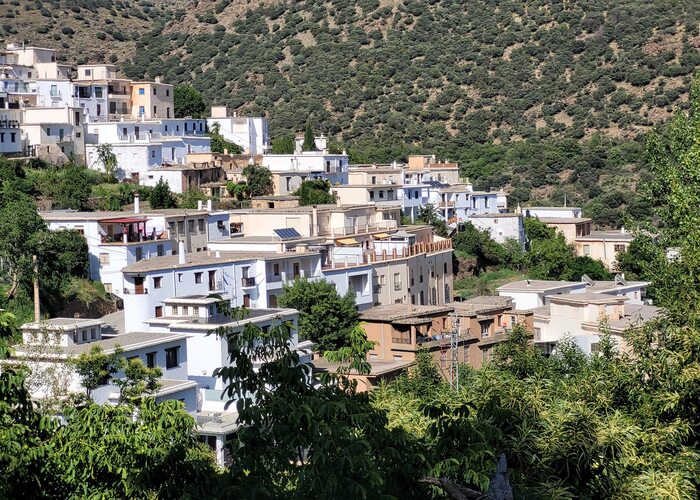

Villages in the Alpujarras have the typical whitewashed facades of southern Spain that, hung with red peppers, support the flat roofs where long narrow chimneys rise stubbornly into the air. The architecture in the region is largely a perfect reflection of the character of the natural environment through the materials of which it is made. To a large extent, the terraced fields are still worked with donkeys and horses. This is because a more modern way is simply not possible. An extensive network of hiking and cycling trails makes it a paradise for nature lovers. The rippling sound of water dominates everywhere. Countless meltwater rivers, mineral springs and streams find their way through deep gorges and along undulating ridges covered with fruit trees towards the silver shine of the Mediterranean Sea.

Moors welcomed and chased away

Like many other places in Andalucia, the Alpujarras was also inhabited by Iberians, Phoenicians, Romans, Visigoths, Arabs and finally Christians. The area was relatively inhospitable. Therefore, the Moors applied their land cultivation and irrigation techniques from the Rif and Atlas Mountains. For eight centuries, the relatively peaceful and fertile rural existence was rudely disrupted by the arrival of the Catholic Kings. The moriscos (Moors who were involuntarily converted to Christianity) were forced to flee to the Alpujarras. Here they lived relatively quietly for a century. With the arrival of the Christians, the pressure became too great and under the leadership of Abn Humeya, the last king of Al-Andalus, they rebelled against all imposed restrictions.

In 1570 this rebellion was bloodily suppressed by Felipe II. So bloody that the riverbed in question has since been called ‘Barranco de Sangre’ (gorge of the blood). According to legend, the blood of Christians flowed upwards and that of the Moors downwards without mixing. Humeya was executed in Granada and all the inhabitants of the Alpujarras fled across the Strait of Gibraltar to distant places. The area was emptied by the Christians and the land was redistributed among about 12,000 Christian families from the north of Spain who started a new life here.

Poverty

The region quickly changed from a flourishing place into a poor agricultural area. The new residents were unaware of the complicated irrigation techniques of the Moors. They were also unfamiliar with the exotic fruits and vegetables introduced by them. Now castles, olive oil mills and remains of irrigation canals are the most important remains of the Moors.

Gerald Brenan

Times improved when, following the example of the English writer Gerald Brenan, a steadily increasing flow of tourists started. Adventurers who, like Brenan, were looking for an unspoiled environment and an original way of life. The western part of the Alpujarras is a popular weekend retreat for Spaniards and is attracting more and more tourists. A growing group of foreigners has also built a new life here in an inconspicuous way. Here, unlike their compatriots on the coast, they are completely absorbed in local life.

“Una vida de puta madre”

The few Alpujarreños we met along the way seemed very satisfied with their lives. “Tengo una vida de puta madre”! the manager of a restaurant in Trevélez admitted with a broad smile. Nearly half of Alpujarreños would not leave the region. The agricultural lifestyle seems to be partly to blame for this. After all, an agricultural field full of beans or olive trees does not take Sundays or public holidays into account. Most Alpujarreños still live from the proceeds of small-scale agriculture.

In the higher part of the Alpujarras, residents often still work their small pieces of land by hand or with the help of horses and donkeys. The products harvested here mainly consist of almonds, olives, grapes, beans, avocados and tomatoes. Many residents or idealistic newcomers also earn a living by maintaining regional handicraft production. The typical colourful jarapa rugs, woven from small pieces of cloth, adorn the street scene. Countless pots, ceramic bowls, wicker baskets, interspersed with ham, honey and wine, fill the shelves of the souvenir shops.

Emerging tourism

Visitors to the region also regularly need something to eat and an overnight stay. For this they can go to one of the many old inns, renovated cortijos, restaurants and hotels that have been converted into casa rural. Companies are slowly emerging that provide tours through the area on horseback, donkey or 4×4. Hang gliding, rock climbing and more active outdoor sports are increasingly offered during the different seasons.

Architecture

The originally Berber architecture creates a North African atmosphere, which becomes complete when the contours of the Atlas Mountains rise from the Mediterranean Sea in the distance. In the villages on the slopes of the Sierra Nevada, all houses face south. The windows are small and set in walls of stacked stone and earth that are sometimes up to a metre thick. Chestnut beams support the flat roofs covered with slate chips and clay. Of the two floors, the ground floor was originally intended for livestock.

©Else Beekman

What forms the roof for one house is the terrace for the house above it. These terraos are used for multiple purposes. Including to dry tomatoes and figs in September. The strings of peppers hang on the front facades in the basking rays of the sun until well into December. In some villages the houses are connected because the alleys in between are covered with so-called tinaos, a kind of pergolas consisting of wooden beams with reeds in between. These keep out the heat in summer and snow in winter. There are long, narrow chimneys on the roofs. These are covered from the rain by a large flat slate with another stone on top.

Natural life

Due to the large differences in height, the sheltered or unsheltered location behind rugged mountains or in valleys and the proximity to rivers, the variety of landscapes and vegetation is enormous. The Alpujarras is roughly formed by the long valley, which lies from east to west between the coastal mountains and the Sierra Nevada. The valley can be roughly divided in two. The western part around Órgiva and the eastern part in the province of Almería. The differences in appearance are great.

In the west we see steep rocks and deep valleys before the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada. Deciduous trees such as chestnuts and oaks and pine forests form the main part here between the arable fields. The eastern part is wider and more expansive, although here too the snow often remains on the peaks until mid-May. Towards Almería, rough and desert-like rock sculptures determine the image. It is drier here and the soil is therefore more suitable for olive trees, almond and palm trees, various types of cacti and agaves. In the higher areas around the tree line, mainly low shrubs such as shrubs and herbs grow.

Our route through the Alpujarras

There are more than seventy villages and hamlets in the Alpujarras. We drove through the higher part of Lanjarón in the west to the Puerto de la Ragua on the border with the province of Almería in the east. The route is 126 kilometres long. From Órgiva we mainly followed the GR421. The first part of Lanjarón up to Capileira and Trevélez is quite touristy. Further on it seems as if we are driving into history. Here we even come across a mule packed with bales of hay.

The villages are astonishingly deserted. The foreigners, even the English, that we encounter all speak quite good Spanish. Moreover, they all seem to be completely absorbed in the rural life of the Alpujarreños. In stable and dry weather it is possible to drive a normal car up to 2700 metres on a dirt road. This road is connected to practically every village along the route. Especially because of the high perspective, this seems to be a beautiful, alternative route.

Lanjaron

Lanjarón is located in a very hilly area that is dotted with terraces so typical of the region. The place is also famous for its mineral water of the same name and the spa with medicinal baths. On a rock that typically rises from the landscape are the remains of what was once an Arab castle.

Orgiva

Órgiva is also called the capital of the Alpujarras. This town has long attracted alternative types from all over the world and has become something of a mecca for hippies. They believe that the village is built on good earth rays. the atmosphere is indeed cheerful and noticeably busy in the sunny streets. We don’t see any hippies, but we do see some jewellery and other craft trinket stalls. Near Órgiva is the Buddhist center O-Sel-Lin (place of clear light). It was opened by the Dalai Lama and even produced his possible successor. The Spanish boy O-Sel-Ling was recognised at the age of five as the reincarnation of a Tibetan spiritual leader and then brought to India for a special education in a lama monastery.

Pampaneira & Bubion

On the way to Pampaneira we see a cave that was once used by shepherds. It looks like the space now mainly houses young people with a romantic mood and wanderers. From the viewpoint on the other side we look down on Órgiva in the depths against an imposing backdrop of mountains.

Pampaneira is probably the most touristic place in the Alpujarras thanks to the awarding of a number of tourist prizes in the recent past. With an abundance of shops bursting with pots, bowls, rugs and ham and many restaurants on cute, atmospheric squares, this is a good place for the day tripper. A little higher on the same slope, Bubión is white amidst flaming autumn hues, which continue to dominate the entire tour despite the fact that it is already December.

Capileira

©Else Beekman

We saw Capileira – called the gate of the Sierra Nevada – against the mountain from below. It is quieter here, despite the fact that the town is a textbook example of typical Berber architecture in the Alpujarras.

Most routes depart from here towards Mulhacén, the highest mountain on the Spanish mainland. The 300 kilometre long route around the Sierra Nevada, the Sulayr route, also passes here. This is part of the GR-240.

Hiking enthusiasts who would like to explore higher altitudes cannot ignore the local information center. The highest, passable road in Europe also departs from Capileira. This runs under the top of the Mulhacén to the top of the Veleta. When too much rubbish was left behind and the Sierra Nevada was declared a National Park, the road was closed to traffic. Nowadays, real fanatics with strong leg muscles still cycle. The ethnological museum gives an interesting picture of how the Alpujarreños lived in the area over the centuries.

Pitres

We follow the road towards Pitres. In a bend, two black-coloured rocks at the Mirador de las Palomicas, rise dramatically above the depths of the valley where the Trevélez and Poquiera rivers meet the Rio Guadalfea, which then meanders its way towards the Mediterranean Sea. Behind, the previous villages are now just three white spots in a row against the imposing snow-capped peaks of the Sierra Nevada.

Ferruginous springs in the Alpujarras

Just past Pitres, next to a charming church, we find one of the many springs (fuente agria) where iron-containing water flows out of the rock wall through four taps. After the first tantalising taste sensation, it’s not really that bad. The water flows down a waterfall and ends in a fairytale-like small gorge where orange-brown is the dominant colour. The iron gives everything that touches the water a rusty tint and the autumn leaves add an extra touch. Breathtaking. This is also the case with the stairs to the top. It is not until we climb them that we first notice we are far above sea level.

Past the village of Portugos, we see the hamlet of Ferreirola in the depths of the riverbank, where there is also a mineral water source. Busquistar is located in a wooded area, but after this town the area becomes wider and the vegetation becomes less.

Trevélez, highest village in Spain

©Else Beekman

We continue along the left side of the valley carved out by the Rio Trevélez to the highest village in Europe. Trevélez is located at 1476 metres. Furthermore, it is even said that the highest point in Barrio Alto is 1600 metres.

Trout still swim in the river and Trevélez ham is world famous. All hams from the area are brought to Trevélez to dry in dim barns in the dry, cool and healthy mountain air.

It is lunch time and we walk into the first restaurant we see. It is dark and freezing and a television blaringly spews the sounds of a bad B-movie through the room. Fortunately, even at this time of year it is still nice to relax on the sun terrace.

Plato alpujarreño

When we ask for the menu, the owner is already busy cooking. His cook sprained her ankle, so today he prepares two platos Alpujarreños himself: two fried eggs, two pork tenderloins, a slice of ham, black pudding and fried potatoes. Presumably a very solid, energy-rich base for climbing the roof of Spain, only slightly less suitable for vegetarians. According to Antonio, most people in Trevélez live from the ham dryers or from tourism. He himself owns a number of horses with which he takes tourists on trips through the mountains. The lower part of the village (barrio bajo) is indeed packed with ham shops and restaurants.

Juvilez

Around Juviles the landscape becomes significantly more desolate and appears less fertile because few deciduous trees grow. This makes the view wider. Nearby are the ruins of the Juvilez fortress from the thirteenth century. This was the first Moorish fortress and in the Middle Ages also the most important in the entire region. With eight watchtowers, its strategic location offered protection to all residents of the area.

The road winds beautifully past the hamlet of Alcuacute to Bérchules. There are no fewer than four fountains here and outside the town there is also a source with ferruginous water. This is beautifully situated between chestnut trees and accessible via a wooden bridge. Here, as in various other villages, there are still some communal washing places in use. The village of Mecina Bombarón is intersected by small ravines that separate the neighbourhoods and is sheltered between mountain walls covered with deciduous trees. Beyond the village, an Arab bridge still stands over the Mecina River.

Yegen

In Yegen we look for the traces of the English writer Gerald Brenan who settled here in 1920 and wrote several books, including the famous South from Granada, which has also been made into a film. Small steep streets are very picturesque to walk through, but problematic when it rains. A gallant villager saved a lady who could not leave the village as her car kept skidding on the slippery road surface. At the house where Brenan once lived, only a plaque from the municipality commemorates him. When we want to buy a bottle of water at a small bakery, we are surprised. Delicious water flows from all the fountains in the village. But who drinks water at this time of the day when everyone is drinking wine? It was five past eleven in the morning.

According to another resident of the village, the publication of Brenan’s book ‘South from Granada’ was not good for the village. He gave the impression that every woman sold herself for a few eggs and a chicken, while that was of course not true. Ok, with a few exceptions then. The positive effect of the book has been that it has attracted quite a few curious tourists to the village over the years. A number of Englishmen, following Brenan, have settled there permanently.

To the other side of the Sierra

We barely see anything of the next four villages on the way to the Puerto de la Ragua mountain pass. This is because it has started raining ridiculously hard and we are also driving through the clouds. We hope to rise above it higher on the pass and still get an impression of the surroundings.

The route seems to be a pleasure for the eyes. At the beginning of the pass there is a warning about slippery road surfaces or snow on the road. Sometimes the pass is completely closed due to heavy snowfall. At the highest point there is actually snow and a recreation zone. Here you can practice cross-country skiing or go sledging. And the restaurant, which immediately makes us feel we are in a ski hut in Tyrol, offers drinks and food. A little further on, the valley of Gaudix and Granada look cloudless.

Also read: Forgotten villages in Andalucia