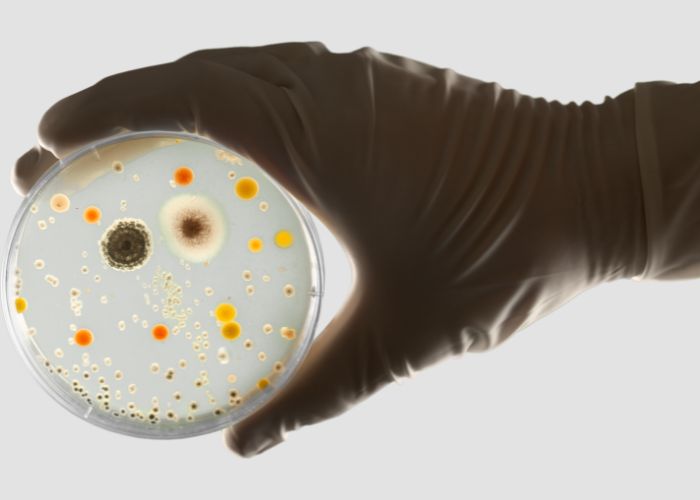

MADRID – Experts have been warning for years about the increase in infections caused within healthcare facilities by bacteria that are immune to multiple drugs. As such, they speak of the ‘silent pandemic’ of antibiotic-resistant microorganisms.

Consequently, a study was conducted in fourteen care institutions in Tenerife. Furthermore, this showed one in ten users of these nursing homes to be carrying antibiotic-resistant super bacteria. It concerns a “remarkably high” colonisation rate of the so-called carbapenemase-producing enterobacteria. Moreover, they are multi-resistant to antibiotics and have a high transmission capacity.

Silent pandemic

Experts, according to El Diario, point out that the increase in infections within those health complexes is caused by evolved bacteria with altered DNA to the point where they generate shields that make them immune to multiple drugs.

Surgical procedures, invasive techniques or episodes of bacterial contamination during cleaning and hygiene tasks in hospitals can cause so-called Health Care Related Infections (HAIs). Thus increasing the length of stay of patients in centres and increasing the number of deaths.

Related: Spain preparing a health master plan for future pandemics

However, hospitals are not the only environment of concern to the scientific community. Specialists from the Microbiology and Infection Control Department of the University Hospital Canarias (HUC) recently published a study in the journal Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. This study analyses the prevalence of colonisation of multidrug-resistant microorganisms among all users of fourteen health centres in northern Tenerife. Ten of these are public.

Tests were carried out on a total of 760 residents between October 2020 and May 2021. Almost 10% (71) were found to be carriers of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, which are of most concern in terms of health.

“Remarkably high degree of colonisation”

This is a “remarkably high rate of colonisation,” emphasises an article by Manuel Callejón. Callejón is a doctor in the hospital complex. Furthermore, he states that the users have been colonised and not infected by these multi-resistant bacteria.

“A person without risk factors can be colonised on the skin or mucous membranes by a multidrug-resistant microorganism without posing a risk to their health. Once a person who has been colonised enters a hospital and undergoes an invasive procedure, for example, catheter insertion, urinary catheterisation, mechanical ventilation, the bacteria can enter the bloodstream or a cavity and infect,” explains María Lecuona, head of the HUC’s Microbiology and Infection Control Department and director of the research project.

The study focused on some gastrointestinal microorganisms. Those are the ones that “cause the most concerning infections in hospitals,” says Lecuona. Moreover, these bacteria have developed a resistance mechanism that makes them immune to a large number of antibiotics.

In addition, they can be transferred to other bacterial families by mobile genetic elements. “If it is not known that there is a patient colonised by this type of microorganism, it can be transmitted in the hospital through the hands, through the environment. Especially if there are no cleaning or sophisticated means of prevention…”

Abuse and inappropriate use of antibiotics

The WHO has been warning for years that antimicrobial resistance is one of the greatest global threats to public health. This is largely caused by misuse and inappropriate use of antibiotics. Also, in a recent study, the WHO warns of drug resistance levels of up to 60% in certain bacteria. Furthermore, the institution predicts the infections caused for this reason will result in 10 million deaths per year by 2050. According to a publication in the medical journal The Lancet, one in eight deaths worldwide in 2019 was related to bacterial infections.

Hospitals are now working with multidisciplinary teams to control the consumption of antibiotics. And thus prevent the spread of resistant micro-organisms. However, these programs are not yet widespread in social health centres and nursing homes.

The specialists of the HUC Microbiology department emphasise that none of the fourteen homes in the study had a specific action protocol to monitor and prevent the transmission of multi-resistant bacteria to anti-infectives.

National Antibiotic Resistance Plan (PRAN)

The ministries of Health, Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge published the third National Antibiotic Resistance Plan (PRAN) in September. In 2019, they have set up a working group specifically to address the optimisation of antibiotics in social care centres. However, the Covid-19 pandemic came and interrupted the activity.

In the next two years, according to the plan, the working group should develop a “framework document” with an analysis of the situation of social health centres. One block devoted to prevention of infections and another to the implementation of programs to optimise the use of antibiotics.

“Important Reservoirs”

The HUC microbiologists state in the recent study that increases in life expectancy and the resulting ageing of the population have made nursing homes an “essential” part of the health system. The results of the study confirm the “high prevalence” of colonisation of resistant microorganisms in social health centres. Therefore, they conclude that these environments constitute “important reservoirs” of superbugs and a risk factor for their transmission and ultimately for public health.

In these nursing homes, people with chronic diseases, people with disabilities and the elderly are cared for. Many of them have multiple pathologies. These people represent a high-risk population. And are, therefore amenable to undergoing colonisation screening for multidrug-resistant bacteria at the time of hospitalisation. This would make it possible to “identify, isolate and treat positive cases”.

“It is absolutely impossible to screen all patients who come in. Therefore, we have to focus on the most vulnerable. That is where most infections will take place,” adds the director of the research project.

Transmission within these residential environments may be due to factors such as the use of “high-pressure antibiotics, permanent living in a confined environment, or difficulty in diagnosing atypical infections,” as well as deterioration in users’ general cognitive functions.

Standardised protocol and alternatives

The specialists confirm the need to establish a standardised protocol between acute care hospitals and social health centres to treat these carrier patients and to implement antimicrobial administration programs and preventative infection control measures in homes.

Early detection of colonised patients is necessary

“What the scientific community fears is that therapeutics will run out if bacterial resistance continues to increase. Therefore, efforts should focus on generating new molecules and early detection of colonised patients to reduce cross-transfer. And also to use the treatments that, although scarce, we still have,” concludes the research project director.