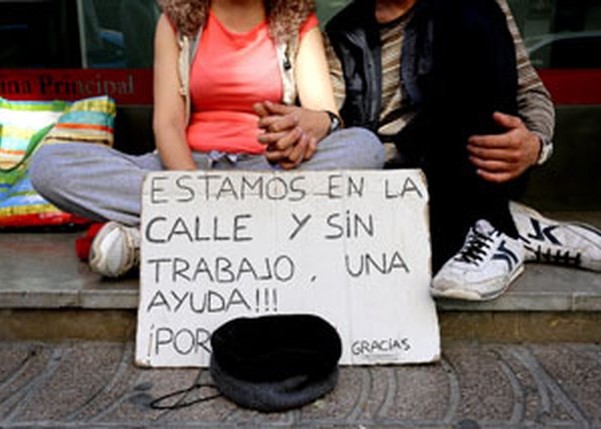

MADRID – The pandemic leaves 2.7 million young people in Spain in a situation of social exclusion: “I could not imagine having to call an aid organisation for food”. These young people live in uncertainty and are often dependent on help for shelter.

According to the latest report by Cáritas and Foessa, the health crisis has revealed that being young (between 16 and 34 years old) in Spain is one of the inequality factors. The study warns that social cohesion in the country has undergone an unprecedented “shock”. A shock that causes “intense and multidimensional” exclusion processes. These prevent young people from growing into adulthood. In addition, 1.4 million young people from this group are in a situation of serious insecurity.

Stopped making plans for the future

Patricia, Verónica, Tamara, Juan, and Jaime Alberto have stopped making plans for the future. All four share the frustration of not being able to solve everyday problems. They are vulnerable because they have no job or a temporary and poorly paid job. They have difficulty finding or keeping a home. In addition, they often depend on help to meet their basic needs such as food. They are just five of the 2.7 million young people in a situation of social exclusion.

Patricia

Patricia is 19 years old and comes from El Palmar, in Murcia, and has just left her job. “I’m exhausted, but I’m happy: I’ve been working in the kitchen of a restaurant since Monday,” she told RTVE.es. She cannot afford the bus to work. Sometimes she waits a long time for her mother to come to pick her up. She lives with her mother and two ten-year-old brothers in her grandfather’s house. The job is for a month. Then she has to look further.

“I stopped studying because I couldn’t afford it. I had to help at home. My mother is a cleaning lady and earns €400 a month. Since she divorced my father, she doesn’t have enough to live on.” Together, Patricia and her mother make it. Patricia feels responsible for the future of her brothers. “There are days when I was hungry and there was no food at home. That’s why I have to work and stay with them,” she says.

More job insecurity with pandemic

According to the Cáritas report ‘Evolution of social cohesion and consequences of Covid-19 in Spain’, job insecurity has doubled during the health crisis. This insecurity about work affects nearly two million households that are economically dependent on one person. Those people have been unemployed for three or more months in the past year, have had three or more different contracts, in three or more different companies,” explains Natalia Peiro, general secretary of Cáritas Española.

The report highlights that by 2021, the number of young people living in an exclusion context will have grown by more than 650,000. Most of them are in a serious situation. There are 500,000 more young people than in 2018 in particularly complex situations.

Patricia belongs to this group who can only think from day to day. She doesn’t know what a night of fun with friends is and she is fully aware of her reality: “I have friends who are better off than me and others who are much worse off. Her goal is to have a home again: “To live in a house of her own with my mother and eat as we ate before.”

Tamara and Veronica

Tamara and Verónica, 33 and 31 years old respectively, are young Spanish women with children. They work, but on what they earn, they can’t get by without help. The Foessa report confirms that social exclusion in female-headed households has increased from 18% in 2018 to 26% in 2021.

“I wake up every morning frustrated because I don’t have enough to live on,” Veronica says. She is from Cartagena, is 31 years old, and works in a greengrocer’s shop. She has two daughters and is in divorce after complaints of abuse. “I’m alone with my two kids. I work long days, but when they get sick, I have to take care of them and I can’t work. The days I don’t go, I don’t get paid and I don’t have anyone to help me ‘, she says.

Veronica has not yet been able to gain access to a home and regrets that she has been told for “a year” that she does not meet the requirements. She lives in the attic of a friend’s house, to whom she pays €150 in rent. “Every month I need help to eat or cover some pharmacy costs,” she confesses. “As a last option, I asked Caritas for help getting access to a home”. Unfortunately, they were also unable to pay three months’ rent in one go, as was demanded.

Tamara works in a retirement home but is on leave for three months due to health problems caused by complications from an operation. That’s why she now earns less. “Normally I earn €900, now with sick leave it is €300 less and my rent is €500”, she calculates. With the rest, she has to pay for electricity and water, school meals, and whatever else she needs for her son, who worries her most.

Juan

“Juan Sebastián Díaz is Colombian and arrived in Spain four months ago. He took an active part in the protests of student and social leaders in his country was a member of a political party and received several death threats. “I took my savings and came to Madrid. I applied for asylum, but I still don’t have the documents to work,” he says. He uses this time to train, while his savings are running out. Cybersecurity course on the campus of the Social Employment Service in Madrid.

Households with foreigners hit harder

According to the study, more than 50% of households with foreigners were in a situation of social exclusion in 2021. The uncertainty experienced in this group is almost three times greater than in Spanish households. Juan Díaz shares a flat and a room. “I don’t know how long it will take before they give me the papers, I just have to study hard and live on the minimum,” he says.

Even more decisive in the intensification of social exclusion is the role of ethnicity. Last year, more than 70% of Roma households were in this situation. This figure triples the figure for Spanish households. Many Roma children suffer the direct consequences of exclusion.

The digital divide: “I don’t have WiFi at home”

The COVID-19 crisis has also exposed a new factor of social exclusion: digital disconnection, the new illiteracy of the 21st century.

Juan

Juan is 35 years old and has been working as a delivery man for a month. He was working in construction when suddenly ‘everything fell silent’. “I couldn’t continue with education at that time because I couldn’t even connect from home. Social workers sent me to this centre. I studied and got a job, he says. From what he earns, he still can’t pay for an internet connection, but he manages: “I have a €10 balance for the whole month.”

Digital blackout

Half of the households in social exclusion suffer from the digital blackout, says FOESSA. That means that 1.8 million households experience the digital divide every day. This mainly concerns households with people older than 65 years. Above all, an internet connection is missed by those who have school-aged children who often have to do something digital.

Yet the main priority for Patricia, Verónica, Tamara, Juan, and Juan remains to provide at least one plate of food a day and to keep a roof over their heads.