MADRID – A quarter of the best-selling ultra-processed products in Spain score well in NutriScore, the future labelling that the Ministry of Consumption plans to introduce this year.

This is according to a report from the El Coco application. It analysed 164 types of food from the 48 most sold brands. The food traffic light only values the nutrients per product and not the degree of processing. Consequently, the Ministry of Consumption does not rule out the possibility of NutriScore being supplemented with another system in future.

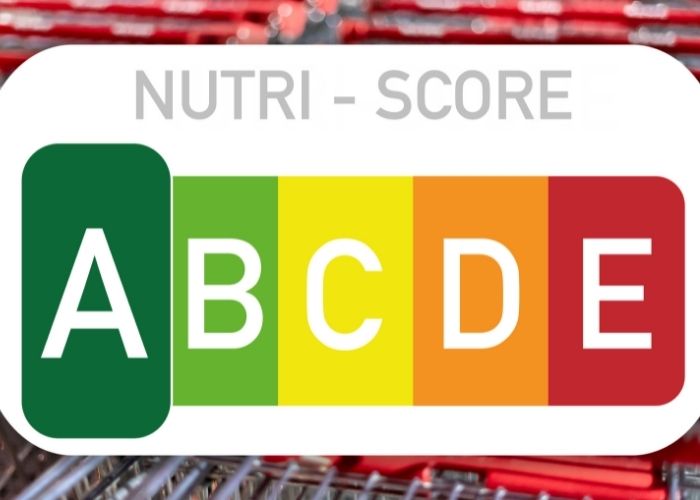

NutriScore traffic light label system

NutriScore is a traffic light that is placed on a product’s front label. Foods that have an A and B in the NutriScore are considered healthy.

El Coco’s nutritionists selected some of the best-selling products in September. They then compared their Nutri-Score rating to their degree of processing; 5% of ultra-processed products get an A, while 22% get a B.

Unhealthy products with good marks on the food traffic light include sugar-free soft drinks, flavoured mineral waters, sliced and pre-packaged bread, mini tostadas, fish fingers, instant cocoa or sugar-free cookies. Meanwhile, extra virgin olive oil gets a C, something the olive growers are not happy about.

What does ultra-processed mean?

The key is to define what ultra-processed is, as there is no legal definition. The industry stresses that this term does not exist and does not want the term to be used at all.

Scientists often use the Nova system, created in 2010 by the University of Sao Paulo. This categorises food into four groups, from 1 (raw) to 4 (ultra-processed). Ultra-processed foods are “products with additives that change the characteristics of the food. These include colorants, sweeteners, thickeners. Furthermore, they contain more than five ingredients with elements that are not normally present in the kitchen (such as soy lecithin) and generally high in fats and sugars.

The vast majority of ultra-processed products are unhealthy, although not always. “In any case, Nova is the least likely to get it wrong when classifying food,” says the nutritionist. In addition, numerous studies link the consumption of ultra-processed products to weight gain and an increased risk of death.

‘Big progress’

The Ministry of Consumer Affairs refers to the statements made by Minister Garzón on this subject a few months ago. “Nutri-Score focuses on the nutritional quality of food, but not on the degree of processing. Implementing this food traffic light is a major step forward. However, it needs to be complemented by other measures based on scientific knowledge,” the minister said in March.

The minister then also pointed out that “the best diet consists of fresh products, fruits, vegetables, which do not get and need Nutri-Score”.

NutriScore’s algorithm ranks negatively a food high in calories, sugars, saturated fats and salt, while positively evaluating the percentage of fruit, vegetables, fibre protein and olive, canola or walnut oil.

Critics believe that the food industry can ‘mislead’ the NutriScore by adding fibre or protein to products, not necessarily making them healthier.

Food labels never complete

Jordi Salas-Salvadó, Professor of Nutrition, referred to the controversy in an interview in EL PAÍS: “Nutrition has many dimensions: one is nutritional, and that’s what NutriScore is about; another is the degree of processing; a third has to do with whether or not it promotes the sustainability of the planet and a fourth is if it contains additives. There will never be a label that can contain all these dimensions. In any case, there are more D- and E-classified ultra-processed foods than A. Furthermore, there is no consensus on the definition of ‘ultra-processed'”.

Voluntary introduction of NutriScore in Spain planned

NutriScore, which is active on a voluntary basis in France, Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland, is already being used by some brands in Spain, such as Carrefour, Lidl and Alcampo. The labelling has sparked scientific controversy, with open letters for and against. Its voluntary entry into force in Spain is scheduled for this year, but some sources say it may be delayed pending the European Food Safety Authority to issue a report on the desirability of applying this frontal labelling throughout the country.